Luciano Pavarotti was born on 12 October 1935 in Modena where he lived throughout his life. (The same year and the same city also saw the birth of one of Pavarotti’s closest collaborators, the soprano Mirella Freni. Their mothers even worked in the same cigarette factory and both Singers claimed to have shared the same wet-nurse: a fact that led Freni to joke that “You can see who got all the milk!”.) His family was steeped in music. His father, Fernando, sang in the city’s chorus, the Chorale Rossini, and soon the teenage Pavarotti was singing alongside him. Indeed, one of Pavarotti’s first foreign trips was with the chorus when it travelled to Llangollen in Wales for the 1955 Eisteddfod when he was nineteen. The Chorale Rossini took first prize in the male chorus category and the young singer had his first taste of acclaim, albeit as part of a group. (Forty years later he would return for a sell—out concert at the 1995 Eisteddfod.)

“From the start I never doubted Luciano would one day be a very great tenor. It wasn’t only the voice, it was his approach to his work — he was dedicated, mature, alert. He wasn’t dabbling, he was totally serious about perfecting his voice.”

Arrigo Pola, Pavarotti’s teacher

Pavarotti: My Own Story

Fernando Pavarotti, who was a baker, had an interesting and appealing voice, but he suffered from terrible stage-fright, but he could clearly see his son’s potential and encouraged him to have lessons. Arrigo Pola was a tenor who had not enjoyed a huge singing career but who was evidently an excellent teacher. He adhered to the old-style craft of not teaching his pupils to sing particular repertoires, but rather of teaching them the art of good singing. He would focus on scales, articulation, how to sing trills stylishly and how to spin a long line where all the notes are produced evenly (what’s known as legato). In short, he was laying down the foundations of a technique that would sustain Pavarotti throughout his life.

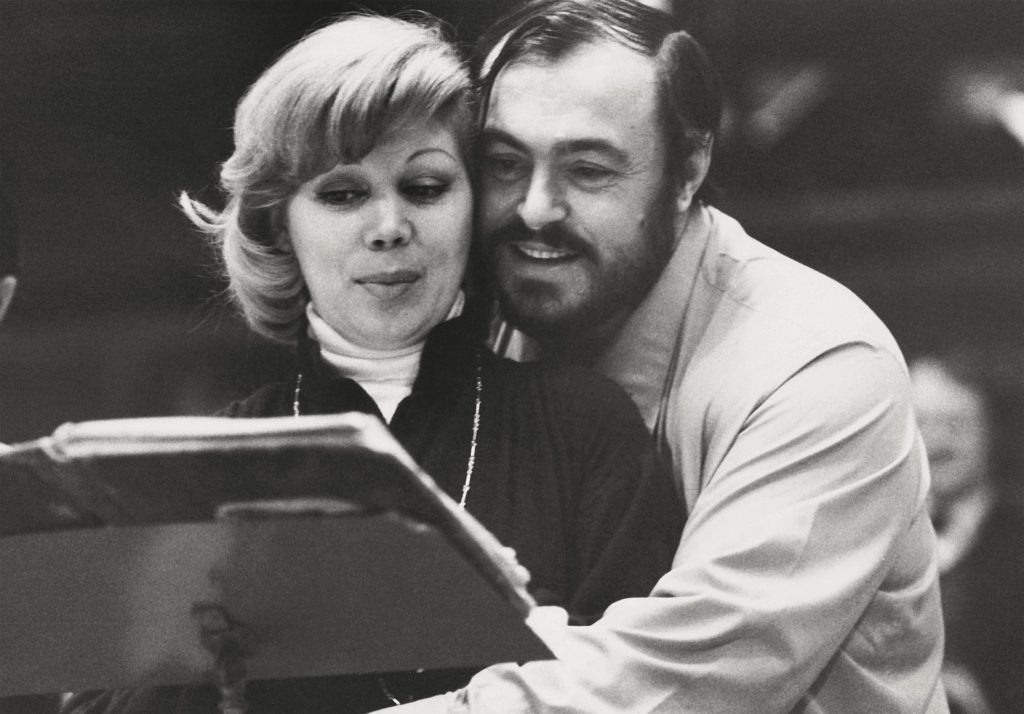

During these years of study, the young Luciano had day jobs: first as a teacher and then as an insurance agent. In 1957, Arrigo Pola took a job in Japan to teach singing to one of the first generations of Japanese who wanted to study Western music. Pavarotti then started to study with Ettore Campogalliani in nearby Mantua. They worked together for three years, during which time the young tenor left his insurance job in order to devote himself exclusively to his singing studies (some days he would travel on the train with his fellow pupil Mirella Freni). lt was clearly a good decision because in 1961 he won the Peri Prize at a competition in Piacenza. This triumph led immediately to his operatic stage debut, as Rodolfo in Puccini’s La Bohème at the Teatro Municipale in Reggia Emilia. The conductor was Francesco Molinari-Pradelli who would later preside over Pavarotti’s debuts at La Scala in Milan, the Metropolitan Opera in New York and in the Arena at Verona.

His debut was a major milestone. The opera house was small so he did not have to force the voice. As a result his sweet, flexible tenor was heard to great effect and the role of Rodolfo would become embedded in his voice and soul as few others. It is one of Pavarotti’s most appealing characterisations: he beautifully blended the world of the innocent, carefree young poet with the heart-breaking discovery as the opera nears its close that his first true love will die in his arms. It is a role that embraces two extremes which both lie comfortably within Pavarotti’s vocal and dramatic armoury.

The next few years were formative. On the advice of his first agent, he studied four key roles: two by Verdi (the Duke in Rigoletto and Alfredo in La traviata), Edgardo in Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor and Pinkerton in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly. These four roles would give him an early taste of the life expected of the late-twentieth-century musician: operatic calling cards would be left in Bari, Bologna, Rovigo, Piacenza and Forli in Italy, then Utrecht, The Hague and Rotterdam. He would sing Rodolfo at the Vienna State Opera and – replacing a singer at the last moment – at Covent Garden. Then it was off to Ankara, Budapest and Barcelona. The peripatetic life had begun.

It was in 1964 that he made his first recording for Decca, the company he was to remain with throughout his career. It was an EP (extended play) disc that contained Puccini’s “Che gelida manina” (La Bohème) and “E lucevan le stelle” (Tosca) alongside three arias from Verdi’s Rigoletto: “Questa o quella”, “La donna e mobile” and “Parmi veder”. Here is the young student who had absorbed the many hours he spent listening to the great singers of the past, but who was determined to stamp his own authority and personality on the music.

Mozart – not a composer immediately associated with Pavarotti – entered his professional life in the summer of 1964 when he sang the role of ldamante in Idomeneo opposite Richard Lewis and Gundula Janowitz at Glyndebourne. It was brought to London for a Prom performance, but more importantly it introduced Pavarotti to the British public and critics (it also introduced him to John Pritchard who would conduct the Decca recording nearly twenty years later). 1964 was also the year that saw Pavarotti sing alongside Joan Sutherland for the first time – his relationship with Sutherland and her husband, the conductor Richard Bonynge, was to be a long and enduring one. Together they played a major role in rediscovering the art of bel canto – an essential technique for those Italian works from the turn of the nineteenth century, orbiting around Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti. It demands a certain kind of vocalism that emphasises technique over volume and which calls for a perfectly even sound production. Sutherland, along with Callas, was one of the pioneers in the re-evaluation of this repertoire and in the young Pavarotti she found the ideal voice — light, pliant and flexible, and founded on a fine technique — to complement hers. She first sang alongside him in Bellini’s La sonnambula and the following year she ensured his US debut by bringing him in to replace an indisposed singer for performances in Miami and Fort Lauderdale. Their musical partnership was to last until Sutherland’s retirement – indeed Pavarotti, along with another member of this small unofficial “company”, Marilyn Horne, was to join Sutherland on stage at Covent Garden at her farewell appearance in the party scene in Die Fledermaus. Both Sutherland and Pavarotti were to record for Decca throughout their careers and together they recorded many of their greatest collaborations

“He [Herbert von Karajan] had an incredible knowledge and memory. Even now when I am teaching, a lot of help is coming from him.”

Luciano Pavarotti, Gramophone magazine